Table of Contents:

During my elective this past semester (a technology course held in our uOttawa’s Education makerspace), I had access to all sorts of incredible tools, from programmable LEGO kits to laser cutters. But I noticed a striking pattern in the lab: while my classmates consistently lined up to use the 3D printers, the sewing machines often sat empty.

This observation sparked a major project for me, and it gets to the heart of how I view inclusivity and technology in education.

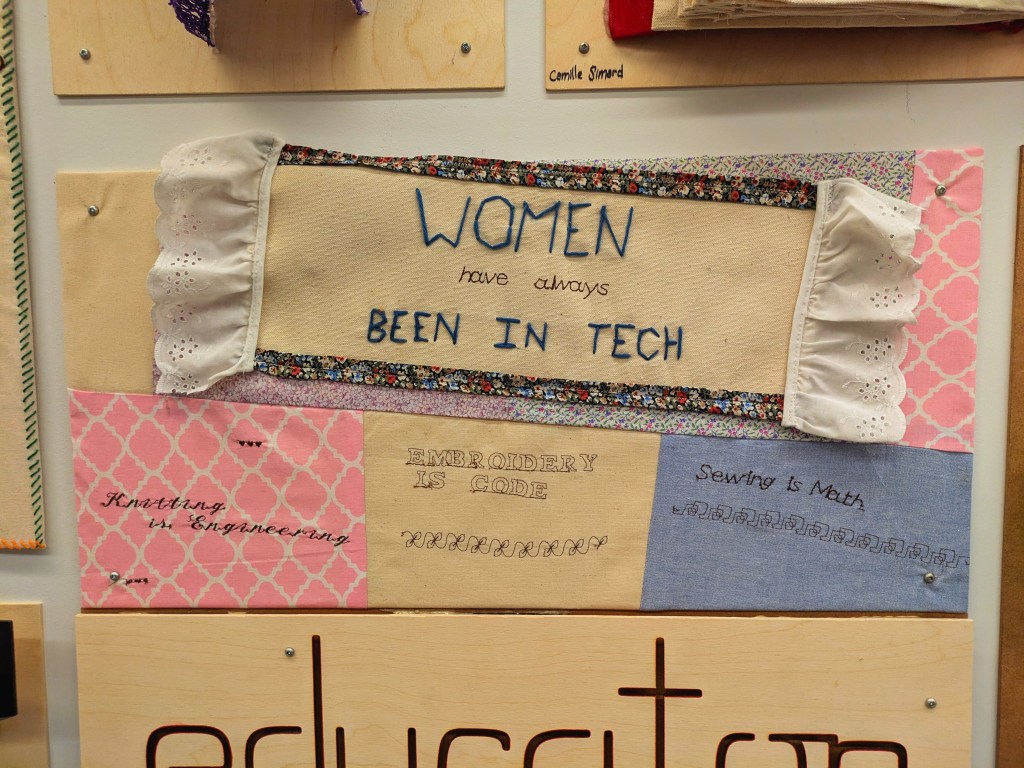

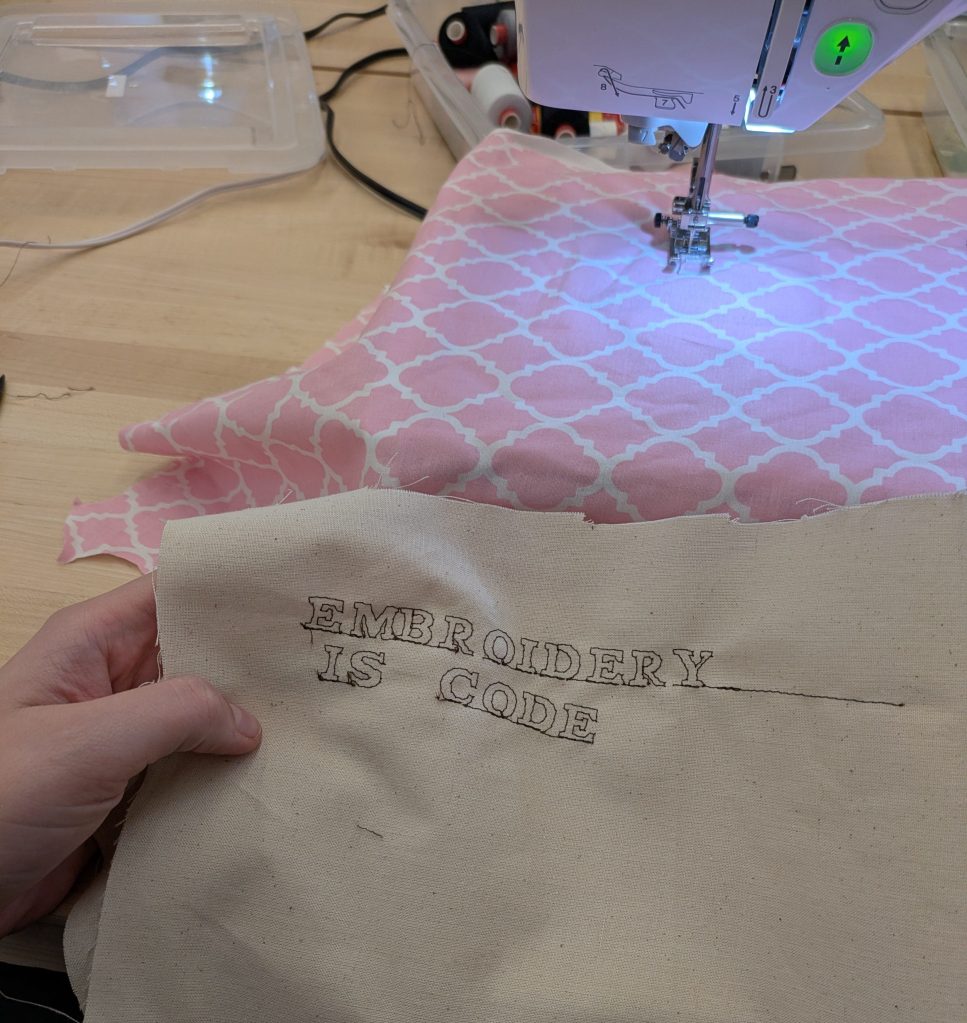

Image Source: Let’s play: Tinkering with tech and transforming education

What is a “Makerspace”?

Before diving into my project, it helps to understand what a makerspace is. Often found in schools, libraries, and universities, it is a hands-on work area stocked with all kinds of materials and technologies. These spaces are incredible: they facilitate learning through play, foster creativity, and directly help students build independence and self-esteem through explorative projects.

I am a huge advocate for these spaces and want to see more of them in our schools. However, I also see a critical need for improvement. These environments often prioritize tools associated with a narrow definition of “tech”, such as robotics and 3D printing. This unintentionally creates a hierarchy where traditional “crafts” are inadvertently seen as less valuable than the “high-tech” tools, impacting who feels welcome in the space.

The Project: Crafting as Technology

For my final art piece, titled “Crafting as Tech,” I wanted to challenge that hierarchy. I created a textile piece that declared: “Knitting is Engineering,” “Embroidery is Code,” and “Sewing is Math”.

And to be clear, I mean that literally:

Knitting is Engineering: Think about the process of creating a sweater out of yarn using nothing but two needles. You are constructing a complex, weight-bearing 3D structure from a single strand of material. The pattern you follow is a blueprint.

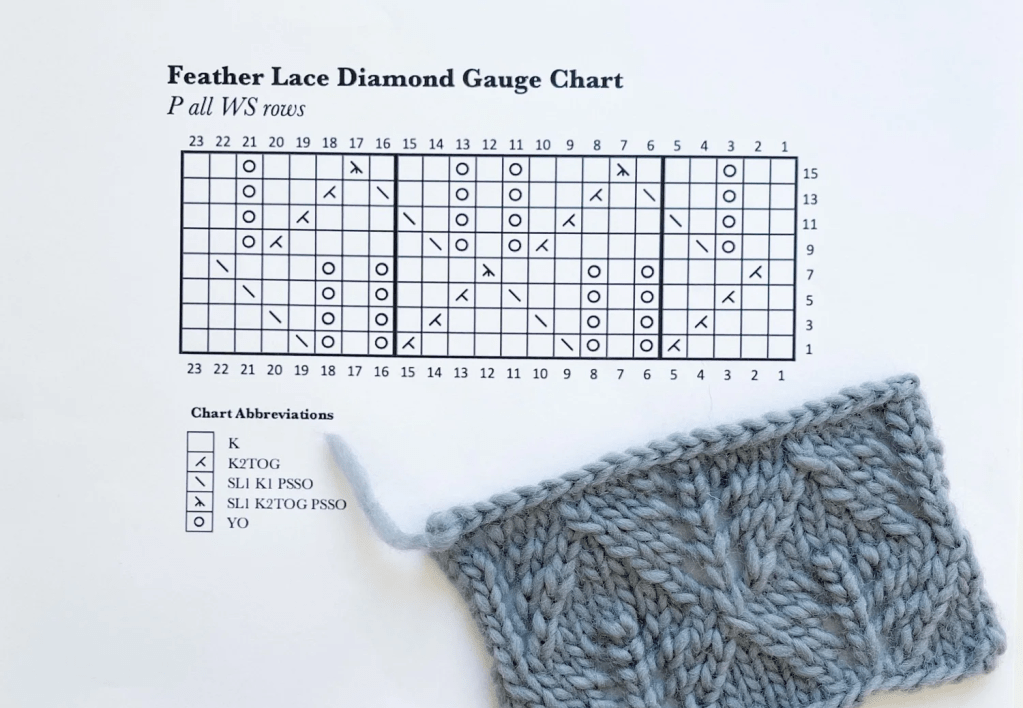

Embroidery is Code: I love to cross-stitch. If you look at a cross-stitch pattern, it is a piece of graph paper with specific coordinates colored in. It is a manual execution of a programmed design.

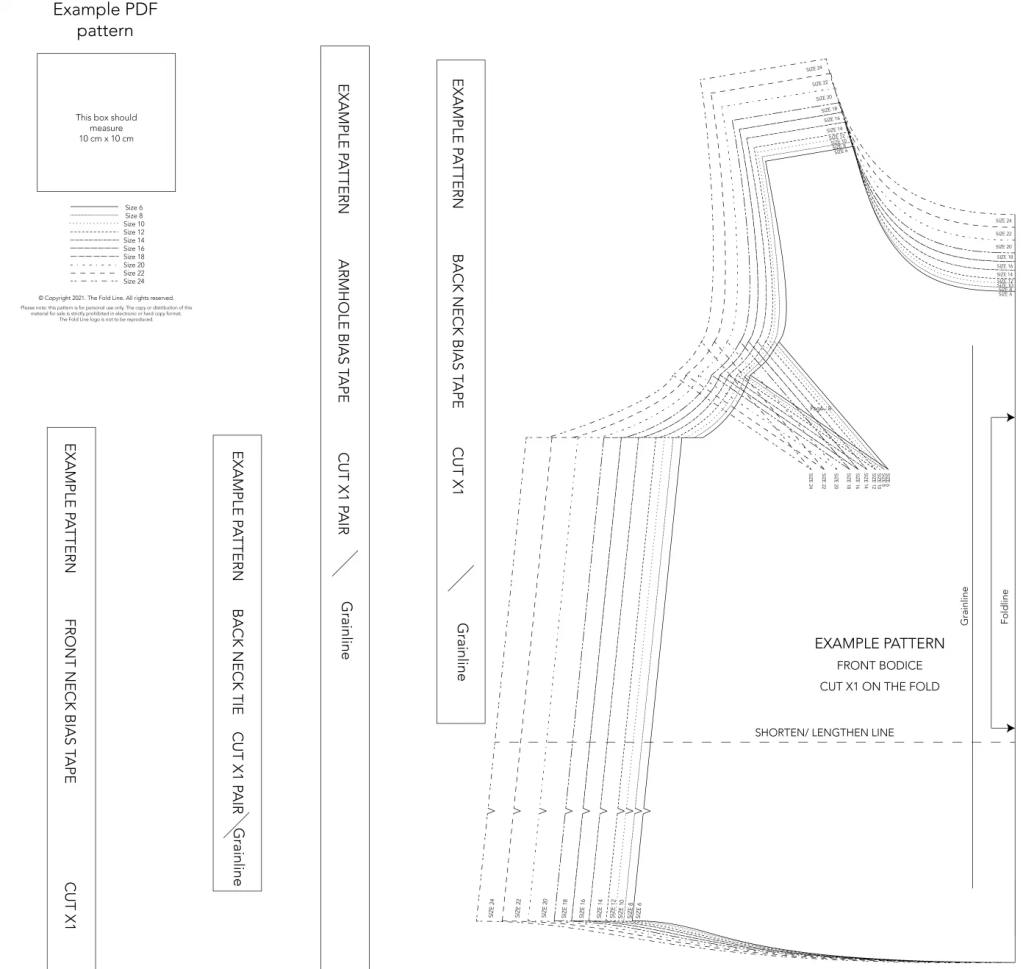

Sewing is Math: This isn’t just about measuring fabric. It involves complex geometry and spatial reasoning. When you calculate seam allowances (fractions) or piece together a quilt block (tessellations), you are constantly solving practical math problems to make 2D shapes fit into a 3D form.

It may seem like a stretch to demand that textile crafts be given the same prestige as engineering and coding, especially if you’re not a part of crafting spaces. But for the women and makers who have always known this truth, it’s an established technical reality that is long overdue for recognition.

My piece asserts that “women have always been in tech,” a claim that is backed up by both modern women who use craft to advance STEM fields and the foundational history of computing itself.

The Mathematician Who Crocheted

If you doubt that crafting is STEM, look at Dr. Daina Taimina, a mathematician at Cornell University.

For over a century, mathematicians struggled to create durable physical models of hyperbolic planes (a complex geometric concept). Paper models were fragile and impossible to interact with. In 1997, Dr. Taimina realized she could solve this by crocheting.

The stitch patterns perfectly represented the exponential growth required for the model. She used a “craft” to solve a problem that traditional technology couldn’t. As she noted in her TEDx Talk, her crocheted models allowed students to literally feel the geometry with their hands; proving that mathematics isn’t just something you see, but something you can experience.

The History: How We Got From Looms to Laptops

It is often overlooked that textile work has always been foundational to computer science.

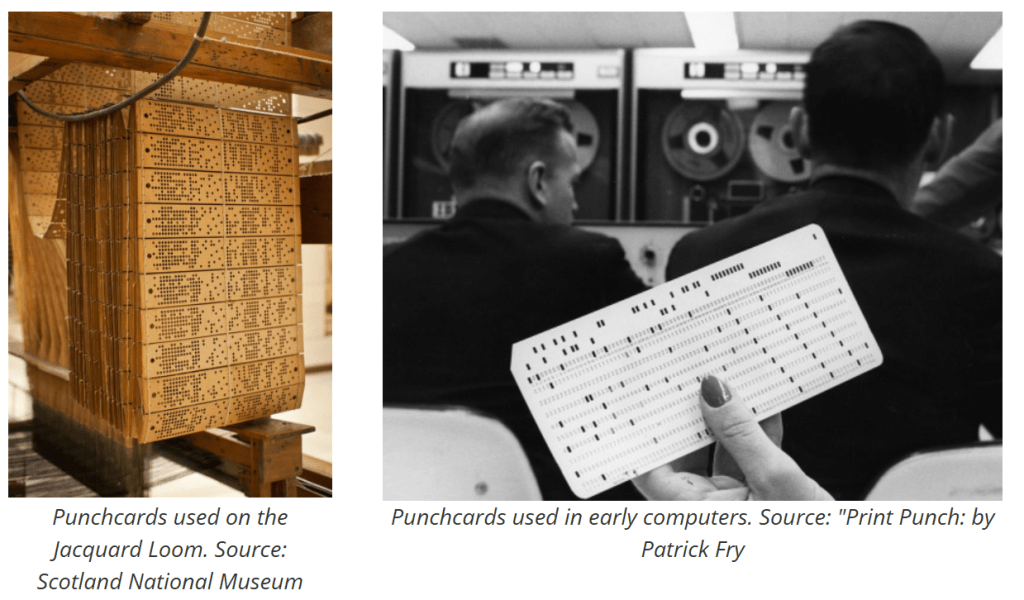

When I developed the thesis for this project, “Women have always been in Tech”, I looked specifically at the Jacquard Loom. Invented in 1804, this loom used a series of interchangeable punch cards to control the weaving of cloth.

The holes in the cards told the machine which threads to lift and which to lower. This on/off system is the direct ancestor of binary code (the 0s and 1s that run our modern computers). The complex algorithms used to weave intricate portraits in silk during the 1800s paved the way for the computer programming we teach today.

My Experience: The Science of Hands-On Learning

For this project, I challenged myself to use a sewing machine with programmable options, a piece of technology I had never used before.

Moving away from screens and keyboards, I revelled in the tangibility of the process. The gentle feeling of fabric under my fingers was a welcome contrast to the hard plastics and screens we usually associate with “modern technology”.

This confirms something I believe deeply as an educator: hands-on activities are crucial because they prompt students to ask deeper questions and retain information better.

And this isn’t just my feeling, it’s backed by science. Studies consistently show that hands-on, active learning significantly improves student performance and retention compared to traditional lecturing.

What This Means for My Future Classroom

As I move into my final practicum, this experience has solidified three key principles for my teaching:

- Broadening Definitions: To make my classroom truly inclusive, I need to integrate the historic technical work of women and diverse cultures. We need to recognize that “tech” isn’t just what happens on a screen.

- Teaching the Process: Whether a student is debugging code or fixing a dropped stitch, the learning happens in the struggle and the solution. I want to teach the process of learning, identifying the logic in everyday life.

- Valuing the Tactile: We need to balance screen time with “making” time. By valuing textile work as legitimate engineering, we allow more students to see themselves as innovators.

My goal is to build a classroom where the sewing machine is viewed with the same reverence as the robot and where every student feels empowered to be a maker.