Table of Contents:

This summer, I travelled to Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand with my sister. It was a dream trip! Seven weeks of markets, temples, street food, and stunning nature. But the experience I want to explore here is one that had me putting on my teacher hat.

In Bangkok, we stayed at a small hostel run by Xi, a Chinese woman who had moved to Thailand for her husband over a decade ago. Xi was commited, not just to running a clean and friendly hostel, but also to using her business to give back to the community. This made for a unique hostel experience as the excursions focused on local engagement instead of hitting the usual tourist hotspots. For example one day a guide took us to a lesser-known market that is known by locals for having the best food in the city. She even explained and suggested dishes for us to try and… she definitely knew what she was talking about! If you ever come across Thai crispy pancakes give them a try. Yum!

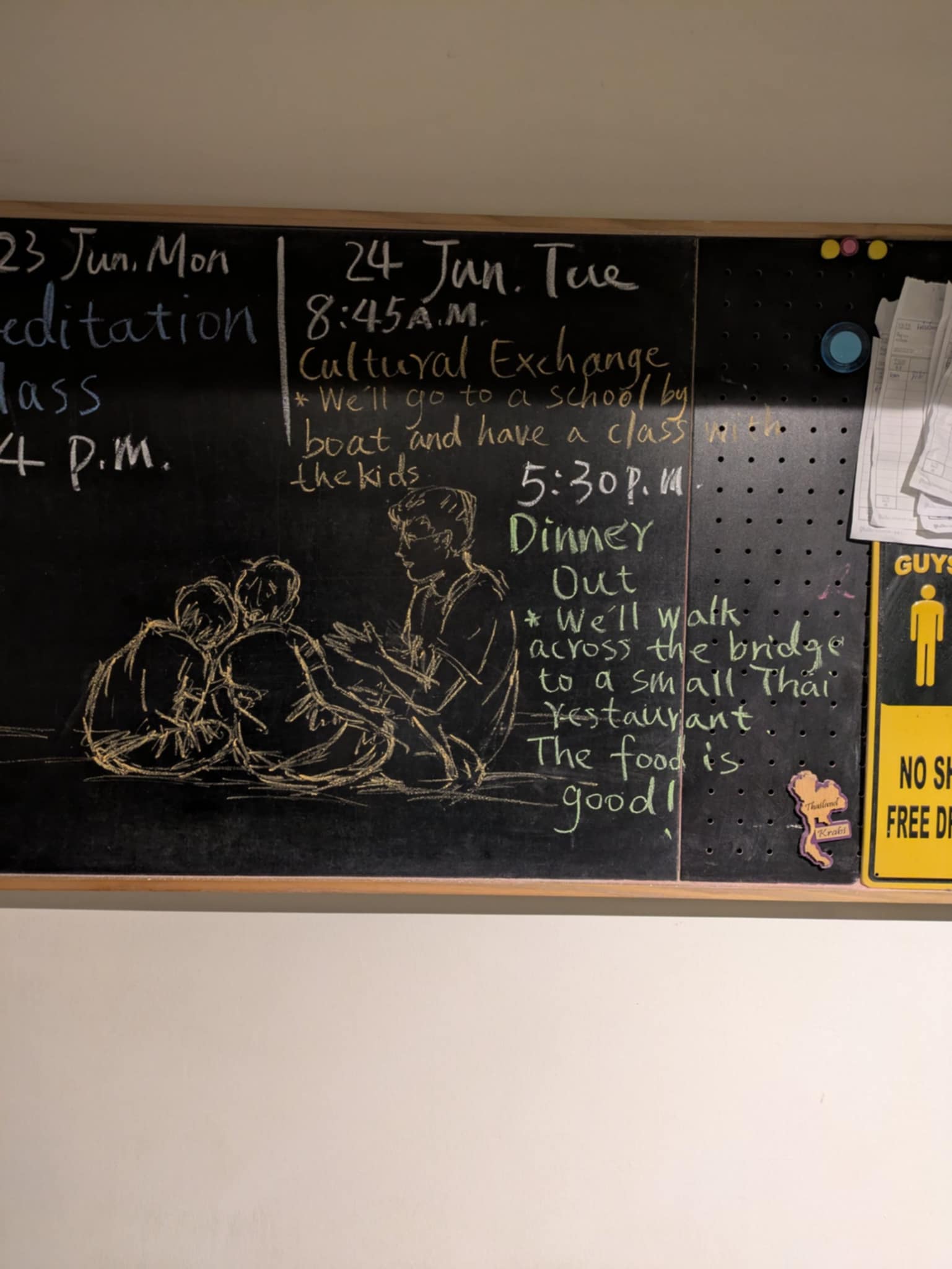

Another one of these activities was a “cultural exchange” with a local elementary temple school and this is what I will be unpacking below.

How do Thai Schools Work?

Xi explained to us that in Thailand there are private schools, public schools and temple schools. Temple schools are located near and funded by a Buddhist temple. The students who attend temple schools are from families that can’t afford the uniforms and books required to send their kids to public school. These schools provide an essential service to the community, students can often be dropped off early and picked up very late to accommodate the difficult work lives of their parents, also by attending they are guaranteed one solid meal that day.

The school we visited was connected to Wat Arun, one of the most famous temples in Bangkok. Despite it being a major tourist attraction, the surrounding neighbourhood was far from wealthy. This is why Xi was trying to improve their education in the small way that she could.

Teaching English in Thailand

In Thailand, English isn’t a national language, but it’s often still taught in schools, why? Learning it can be a big leg up in terms of job opportunities and economic success. Thailand has put a lot of effort into building its tourist industry for years. Think about it, there is a Thai restaurant in every major city and Pad Thai is a globally recognized dish. But can you name a single Filipino, Singaporean or Malaysian restaurant? They are far less common. Thailand has deliberately and successfully exported its culture worldwide and reaps the benefits of a lucrative tourist industry.

This is the goal of Xi’s cultural exchange program, to improve the English of the students. She brings a new group of travelers each week to expose the kids to native English speakers with a variety of accents. She also hopes that by exposing the kids to people from all around the world they may be able to envision a different future for themselves.

My Trip to the Temple School

To get there, we took a water taxi down the Chao Phraya River to Wat Arun, then walked to the school gates. We arrived just as a police officer was giving an assembly about not doing drugs. Which is apparently a big issue even for an elementary school in this neighbourhood.

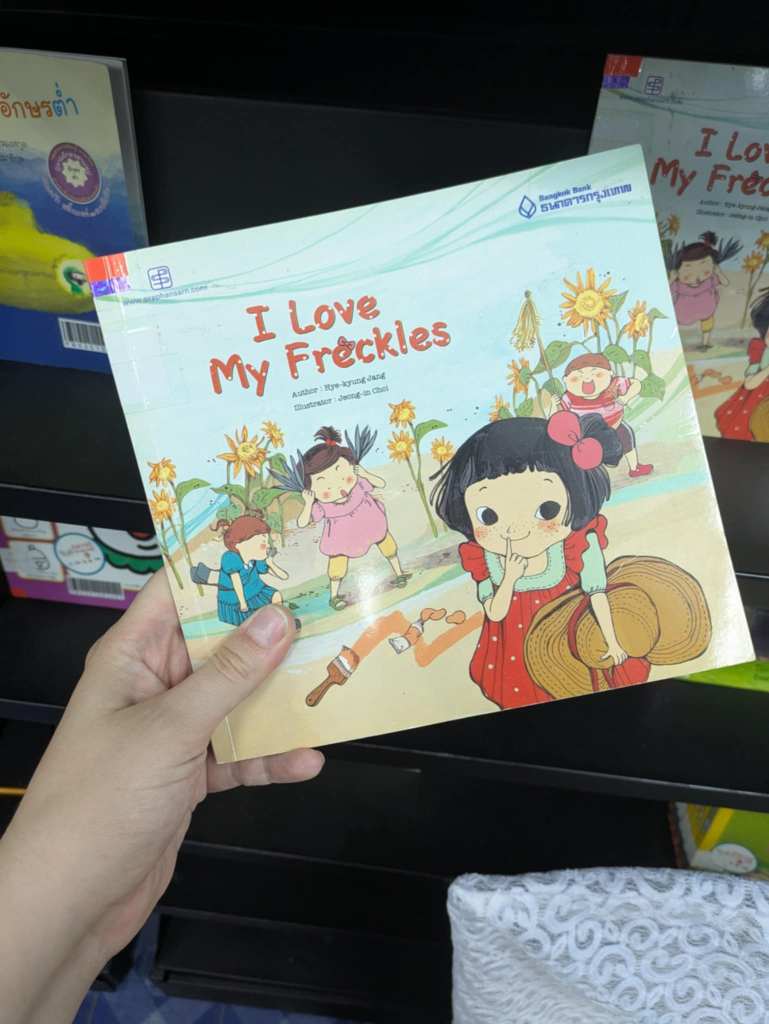

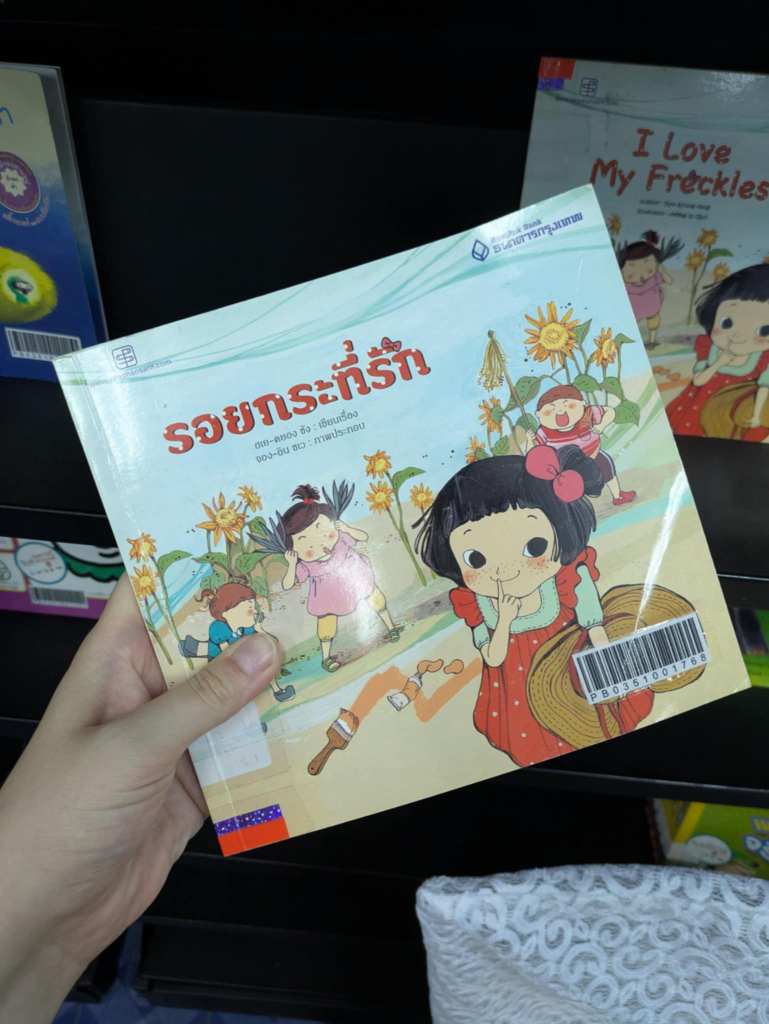

We waited in the library, where I noticed double sided Thai-English books and looked at some teaching matrials. When it was time for our class, the kids did a quick body break, and then we were brought in.

The format was simple. Each of us introduced ourselves: name, age, country, job. The teachers helped translate when needed, and then the students asked questions.

I got:

- “Is it cold in Canada?” I explained that Canada is very big and that we have many seasons and some seasons are very cold.

- “What food do you eat in Canada?” I showed them a photo of poutine and tried to explain cheese curds.

- “What’s your favourite Thai food?” When I said green curry, they clapped. Apparently, anything other than pad Thai gets points for originality.

Afterward, the teachers asked the class recall questions in English: What is her name? Where is she from? What is her job? The students raced to answer correctly so they could earn high fives from the guest speakers for correct answers.

I had a great time. It was fascinating to see how a Thai school operated, and I found myself poring over teaching materials in the library, curious about what and how they were learning. The students were kind, curious, and full of energy. After a flurry of excited whispers, they surprised us by singing a song in Thai!

Spending time with Xi was another highlight. She’s a deep well of knowledge and generously shared insights about Wat Arun, the royal family, and the range of opinions Thai people hold toward the monarchy. Her energy and passion for her community left me thinking about home and my own community and what more I could be doing.

I really hope this program is a genuine asset to their education, and not just a feel-good experience for people like me.

Wrestling with Voluntourism

I’ll admit, I was hesitant about the trip at first. I know how hard English phonics is to teach, and while I’m studying to be a teacher, most of the other participants weren’t. But I was relieved to learn that the goal wasn’t for us to teach grammar or reading but to expose students to native English speakers and diverse people. The real educators were the Thai teachers, and we were just guests in their classroom. Despite this on the boat ride back, I still found myself thinking about voluntourism.

Voluntourism or “volunteer tourism” is when travelers (typically from Canada, the US or Europe) participate in short-term volunteer projects as part of their trip, often in low-income countries. These experiences are typically framed as mutually beneficial: tourists get to “give back,” and local communities supposedly receive support.

When I was in high school, the kids who went on those big Me to We trips to build schools in Africa were admired. But in recent years, there’s been a growing (and I think valid) critique of these experiences. These trips are often more feel-good, white-saviour tourism than meaningful community support. Was I participating in this same charade?

“Transnational feminists have shown that well-intentioned interventions in the South by Northern women can replicate the racial superiority and global asymmetries of previous civilizing missions”

This quote reminds me even if my intentions are good I can still be complicit in upholding harmful power dynamics.

I’m still grappling with how I feel about it all. What kinds of programs are helpful? What kinds replicate colonial dynamics under the guise of charity? Is it even possible to do this kind of work ethically? And more broadly: is all tourism exploitative in some way?

So if you’re considering volunteering abroad, here are some questions worth wrestling with:

- Are you going to be doing work you’re unqualified for i.e. teaching English without a teaching degree, or building schools without any trade skills?

- What makes you more suited for this work than someone from the local community?

- What are you hoping to get out of the experience? Are you seeking connection, or validation? Are you expecting to be thanked, praised, or admired for your efforts?

It can be hard to answer those questions honestly. But as Canadians (and especially as white Canadians), it’s essential that we do, lest we take on the role of modern day colonizers.

I’m not the first person to struggle with these questions, and I definitely won’t be the last. Scholars like Leila Angod have looked critically at how even programs meant to promote global justice often reinforce Canadian exceptionalism. A myth that paints Canada as a benevolent helper while erasing our colonial past.

“I use the term Canadian exceptionalism to describe a national mythology of goodness, generosity, and innocence that erases the violent founding and ongoing making of the white settler colony we know as Canada. […] Canadian exceptionalism encourages the pleasure of knowing ourselves as vulnerable because we empathize with the suffering of others.”

“The moral position here is clear: as empowered Canadian girls their role is to uplift South African youth, a deficit view of Africa as a place“

If you’re at all interested in learning more about this topic I suggest reading Leila Angod’s paper “Learning to Enact Canadian Exceptionalism: The Failure of Voluntourism as Social Justice Education, Equity & Excellence in Education”. Her writing has informed a lot of my own thoughts on the topic and I appreciate the specifically Canadian perspective.

“Northern travel to the South inevitably requires and reifies the basic privilege of mobility (requiring wealth, passports, and the perceived legitimacy of one’s presence) and the ability to exercise one’s gaze upon Others. In this way, there is no neutral starting point.”

There’s no easy way around that. Just stepping onto a plane with my Canadian passport is an act loaded with privilege, one I carry with me, whether I name it or not.

So where does that leave us?

Travel, Privilege, and Paying the Tourist Tax

At the very least, we can acknowledge our privilege as travellers. The privilege of a strong passport. The privilege of a strong dollar.

One of my best pieces of travel advice? Let yourself get ripped off. Seriously. There are hundreds of blogs and TikToks about how to avoid the “tourist tax,” but I say: pay it. If a local vendor charges me a bit more at the market, that’s okay. If someone goes above and beyond in their service I tip, even if it’s not expected in the culture. Being generous often costs me very little, but it can mean a lot more to the person I’m interacting with. Besides there plenty of other (and more lucrative) ways to keep a trip on a budget: staying at hostels, eating street food, tracking flight prices ect.

Final Reflections

I love to travel. I love the way it pushes me out of my routine, the way it fills my senses with new sights and smells and sounds. I love learning phrases in new languages, trying unfamiliar food, and being reminded that the world is so much bigger than my little corner of it.

Thailand was incredible. The street food, the temples, the people, the long jungle hikes… I had an amazing time! And visiting the temple school was part of that amazing experience. It was joyful and meaningful and something I’ll remember for a long time.

I’m not here to take a hardline stance or say that all travel is unethical. But I do think it’s important to critique our own experiences, especially when they involve moving through spaces where we hold disproportionate power. Tourism (especially the kind framed as charity) can reinforce harmful hierarchies, even when our intentions are good.

If I don’t sit with those questions, if I don’t examine my own role in these systems, I risk being blinded by my privilege. And worse, I risk repeating the very mistakes I claim to oppose.

For me, travel is still worth it. But only if it comes with reflection, with humility, and with a willingness to listen and learn.

References

Leila Angod (2022) Learning to Enact Canadian Exceptionalism: The Failure of Voluntourism as Social Justice Education, Equity & Excellence in Education, 55:3, 217-230, DOI: 10.1080/10665684.2022.2076787