Table of Contents:

What is Pod?

My first year practicum experience has been quite different from the typical classroom placement. Instead of being assigned to a school, I am working in collaboration with Ottawa’s Children’s Aid Society (CASO) to support students in foster care and group homes with their schoolwork. The Pod Model for Learning Support Program assigns teacher candidates a list of 10-15 students to check in on, offer academic support to, and tutor as needed. For the safety of both students and teacher candidates, this program is conducted entirely virtually.

This practicum has been an incredibly rich and eye-opening experience. Every student has unique challenges and strengths, which has pushed me to develop adaptable, student-centered teaching strategies. In this post, I highlight one specific challenge I encountered and how I approached it. Naturally, all names and identifying details have been redacted for student confidentiality.

Understanding the Challenge

One of my students is a clever, articulate high schooler who struggles with reading at a sixth-grade level. While their oral vocabulary is impressive—using words like “neurobiology” and “isopod” effortlessly in conversation—they find decoding written words difficult. Once they sound out the word their comprehension is strong, but they rely heavily on context clues and educated guessing to mask their difficulties.

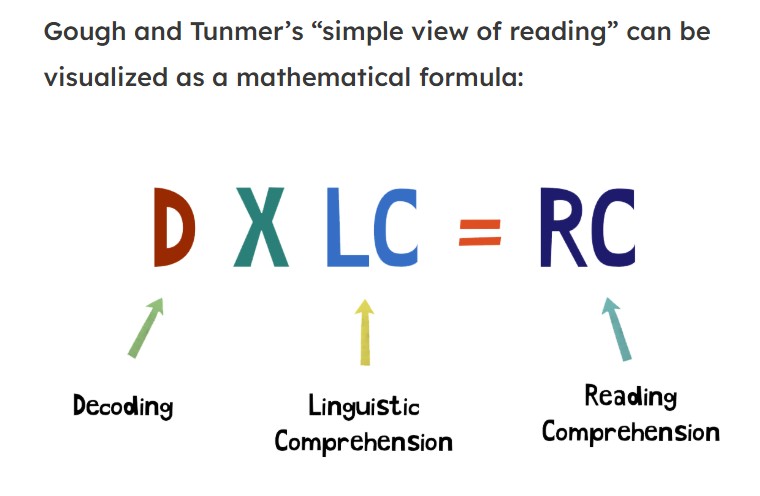

Researching Gough and Tunmer’s “simple view of reading” helped me better understand my student’s varied abilities. The simple view of reading can be understood as an equation where the product of Decoding (D) and Linguistic Comprehension (LC) is Reading Comprehension. In this case the student needs help with decoding “D” but not linguistic comprehension “LC”.

At this point I had two reactions in quick succession: Great! Now I know what we need to work on! and then Wait…how do you teach decoding?

Teaching Phonics

Before this practicum, I had very little experience teaching phonics, so I had to do a deep dive into best practices. Here’s a quick breakdown of key phonics concepts I focused on:

- Phonics: A method of teaching reading that emphasizes the relationship between sounds (phonemes) and letters (graphemes).

- Decoding: The ability to turn written words into speech by implementing knowledge of phonics (ie. sounding out words).

- Phoneme: The smallest unit of sound in a word. English has 44 phonemes. (ie. the letter c has two phonemes /k/ and /s/).

- Grapheme: The written representation of a phoneme (letters or letter combinations like sh, ch, or igh).

- Blending: Combining phonemes together to read a word (e.g., /s/ /t/ /o/ /p/ → stop).

To assess my student’s proficiency with phonemes, I created a set of flashcards featuring words that incorporate each phoneme (see a PDF of my flashcard terms below). Initially, I expected my student to struggle primarily with blended consonant sounds (e.g., st in stop or thr in throw) as I had observed while reading short stories together. However, I quickly discovered that they struggled a lot more when presented with words devoid of context. Instead of sounding out each letter in a word, they would sound out partial letters and then guess at the most likely word it could be. Recognizing this pattern was key to reshaping my approach.

Sources

Quizlet used to create online flashcards: quizlet.com

Flashcards based off Reading Rocket’s list: https://www.readingrockets.org/sites/default/files/migrated/the-44-phonemes-of-english.pdf

The Reading Wars

The debate over how to best teach reading has been raging for over a century, with two major camps: phonics and whole word. But the debate is over, the research is now clear—phonics is the most effective method for teaching kids to read. Despite this, the shift from whole word to phonics-based instruction has been slow, largely because many educators were trained in and strongly supported whole word methods.

The Science of Reading movement pushes for the elimination of whole word instruction in favor of phonics-based teaching for all children. Of course, there are many different versions of both phonics and whole word approaches, so this timeline is a very simplified summary of key events. As the name “the reading wars” suggests, this is a heated and often divisive topic, but I’ve done my best to break it down.

- Before 1930: Phonics is the dominant approach, with some memorization of common words.

- 1930 – 1965: Whole word becomes the standard in the U.S., and children learn to read through simple, repetitive stories (think: Dr. Seuss books).

- 1955: Why Johnny Can’t Read by Rudolf Flesch is published, calling for a return to phonics and sparking the Reading Wars.

- 1967: Even more research supporting phonics is published.

- 1965 – 1975: Some schools begin incorporating phonics again, but others stick with whole word while adding some phonics elements.

- 1975 – 2000: Despite mounting scientific evidence against whole word, a new version of it called whole language takes hold. This approach encourages children to read more complex texts but still relies on context and memorization rather than decoding. It spreads rapidly across the U.S. and Canada.

- 1986: Gough and Tunmer propose the Simple View of Reading in support of phonics.

- 2000: The U.S. Congress’s National Reading Panel releases a report concluding that phonics is the most effective method for teaching reading. The report also strongly condemns the practice of whole word and whole language instruction.

- 2005: Additional global research reinforces that phonics is the best approach.

- 2013: Mississippi overhauls its reading policies to align with the Science of Reading framework, leading to a dramatic improvement in literacy scores.

Sources

The new “science of reading” movement, explained | by Rachel Cohen | Vox | Aug 2023: https://www.vox.com/23815311/science-of-reading-movement-literacy-learning-loss

A Brief History of Reading Instruction | by Stephen Parker | Dec 2021: https://www.parkerphonics.com/post/a-brief-history-of-reading-instruction

If you’re interested in learning more I also suggest checking out the “Sold a Story” podcast by APM reports.

Understanding this broader literacy landscape helped me frame my student’s reading challenges within a research-backed approach.

Implementing UFLI

The resource I’ve found the most useful in lesson planning for this student is the UFLI Foundations Toolbox. All their resources are designed to teach students decoding skills (ie. the “D” from the “simple view of learning” equation) and their materials are in alignment with our modern reading research.

“UFLI Foundations is research-based. This means it was developed to align with what decades of reading research has shown to be effective.”

– University of Florida Literacy Institute

As someone who had never taught phonics before, the progression of the UFLI lesson plans was very helpful. By which I mean they suggest teaching vowel sounds, then certain diagraphs, then VCe words ect. Not all of the UFLI lesson plans are available for free but the entire framework is. By looking at this framework I was able to decide where to start with my student.

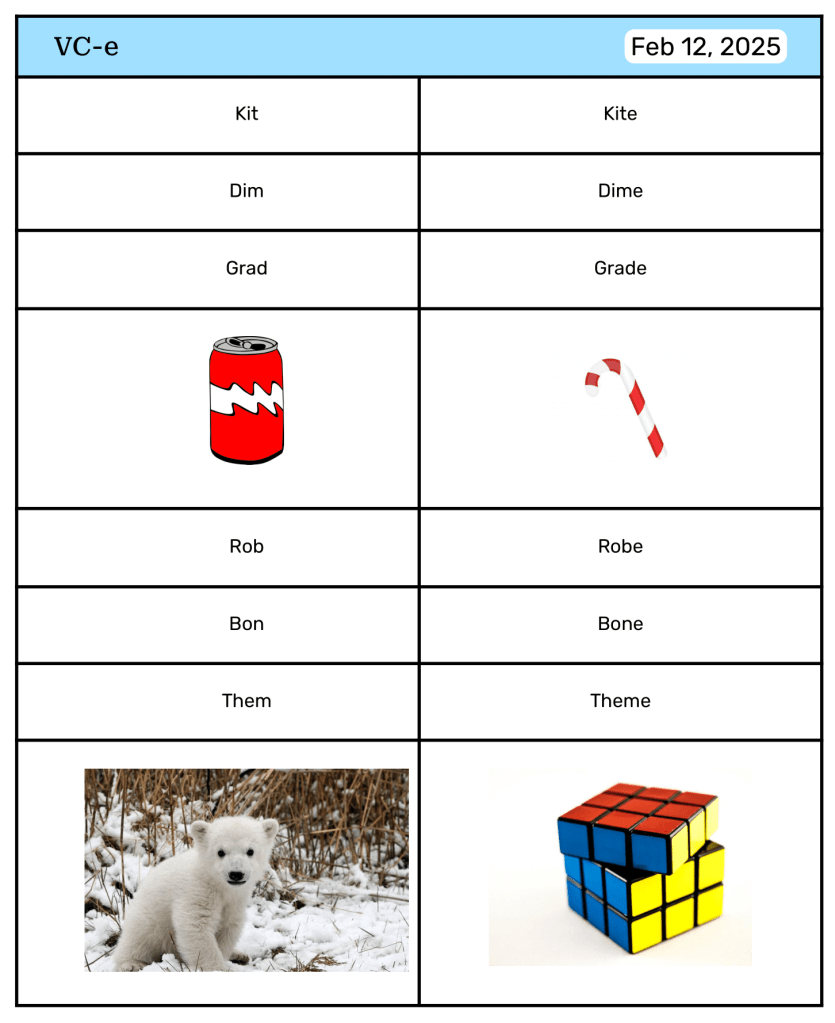

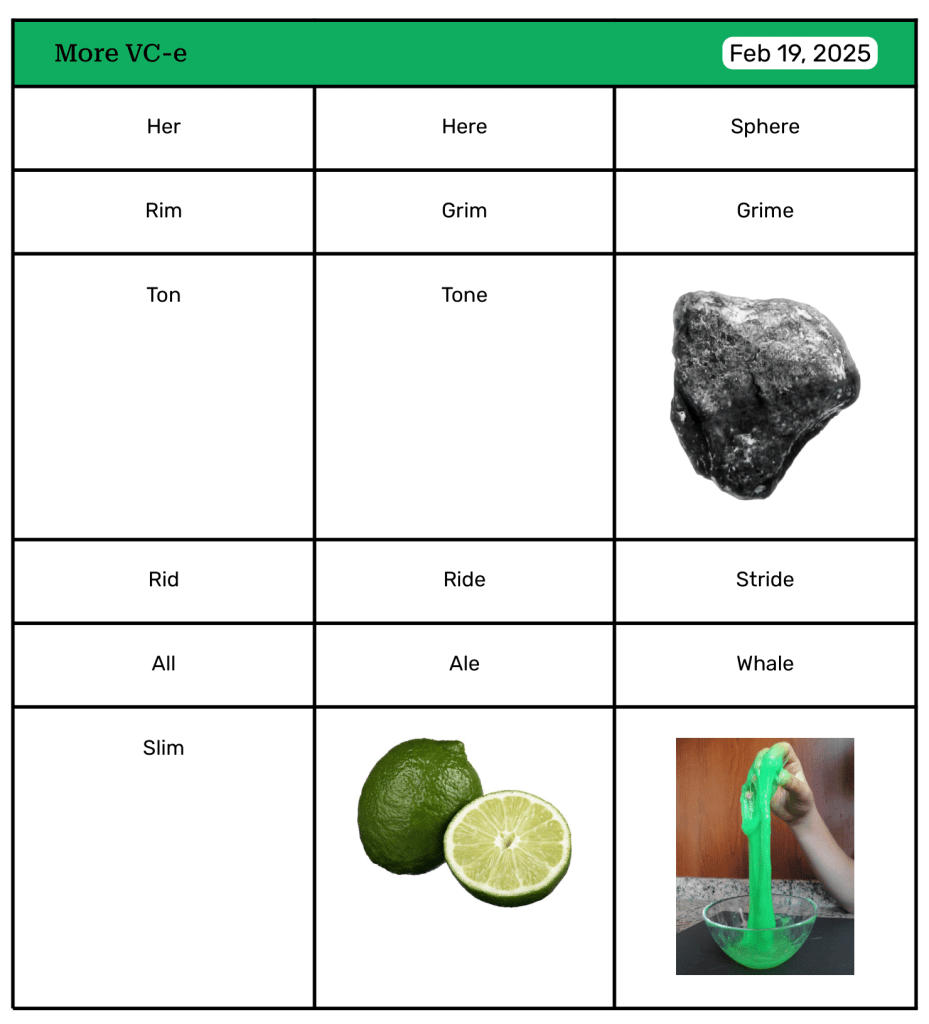

Currently, my student and I are working through Vowel-Consonant-e (VCe) patterns—words where adding an e changes pronunciation (e.g., kit → kite). I created custom materials, including:

- Word lists featuring VCe patterns

- Decodable texts with age-appropriate content

- Flashcards for practicing high-frequency words

Creating Age-Appropriate Materials

One of my biggest challenges has been finding materials that respect my student’s maturity. Looking at worksheets meant for kindergarteners can be demoralizing. To make phonics practice more engaging and age-appropriate, I used the following strategies:

- Graphic Novels & Comics: These provide visually engaging text with manageable reading demands. Many are available for free and through library apps.

- Interest-Based Readings: Before winter break, my student mentioned enjoying the movie Gremlins, so I found an online movie review and used AI to adapt it to their reading level.

- AI Tools for Decodable Texts: I experimented with AI-powered tools like Brisk to simplify advanced texts to my student’s level. While I have ethical concerns about the overuse of AI in education, it was one of the only accessible options for generating age-appropriate phonics materials. For example, I used it to create a short story, The Code, which focuses on VCe words.

My student isn’t the only one facing this challenge. Several students in our Pod program struggle with decoding, yet there is a frustrating lack of phonics-based materials designed for older students. The common response “just use AI” isn’t a sustainable or ethical long-term solution. We need more resources that balance systematic phonics instruction with engaging, age-appropriate content.

Final Thoughts

This practicum has been a steep learning curve, but it has also been one of the most rewarding teaching experiences I’ve had. While I initially lacked confidence in teaching reading, diving into the Science of Reading, phonics instruction, and adaptive teaching strategies has given me the tools to support my students effectively.